The Forgotten Chapter: Clyde Lovellette’s Short Stint with the Celtics and the Number 34

In the annals of Boston Celtics history, a few names shine with an almost mythological glow. Bill Russell, Larry Bird, Bob Cousy, John Havlicek—these are the pillars of a dynasty. Their stories are told and retold, their contributions celebrated and immortalized. But for every legend who defined an era, there are dozens of valuable contributors who played their part in the Celtics’ unparalleled success, their tales often relegated to footnotes. Among this group of forgotten champions is Clyde Lovellette, a man whose brief but impactful career with the Celtics, wearing the now-familiar number 34, is a curious and compelling chapter of basketball history.

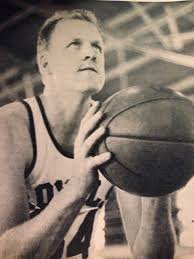

Before his arrival in Boston, Lovellette was anything but a footnote. He was a basketball giant in every sense of the word. Born in Indiana, he made his name as a legendary big man for the Kansas Jayhawks under the tutelage of the iconic coach Forrest “Phog” Allen. He was an unstoppable force in the post, a high-arcing jump shooter, and a tenacious rebounder. In 1952, he led Kansas to the NCAA championship, winning the tournament’s Most Outstanding Player award. His college career was so dominant that he became the first player in history to win an NCAA title and an Olympic gold medal in the same year, a feat he accomplished with the U.S. national team.

Lovellette’s star continued to rise in the NBA. Drafted ninth overall by the Minneapolis Lakers, he joined forces with another titan, George Mikan. Lovellette spent four seasons with the Lakers, winning his first NBA championship in 1954 and establishing himself as one of the league’s premier scorers. A true workhorse, he averaged over 20 points per game in two of his seasons with Minneapolis, showcasing a rugged post-up game that was a throwback even in that era. He later played for the Cincinnati Royals and then the St. Louis Hawks, where he continued to be a prolific offensive weapon, earning multiple All-Star selections and building a reputation as a player who could get a bucket whenever his team needed one. By the time his career with the Hawks concluded in the early 1960s, Lovellette was a veteran with a championship ring and a resume that had already cemented his place in basketball history.

His path to the Boston Celtics was both unexpected and, in many ways, an acknowledgment of his unique skills. By the 1962-63 NBA season, the Celtics were in the midst of a dynasty that was unprecedented and, to this day, unmatched. They had won four of the last five NBA championships and were a machine built on unselfishness, relentless defense, and a fast-breaking offense. The team was anchored by Bill Russell, the greatest defender in the history of the sport, and surrounded by a constellation of stars and role players like Bob Cousy, Sam Jones, and the emerging talent of John Havlicek.

The Celtics’ weakness, if they had one, was depth in the frontcourt behind the immortal Russell. When Russell needed a break, the team’s interior defense could suffer, and their scoring off the bench from the big man position was often inconsistent. To address this, legendary Celtics coach and general manager Red Auerbach made a shrewd and calculated move. Before the 1962-63 season, he acquired the 32-year-old Lovellette from the St. Louis Hawks in exchange for Jim Krebs. The trade was a quiet one, a mere footnote in a star-studded offseason, but it was a masterstroke of roster construction. Lovellette was no longer the star he once was, but he was exactly the kind of player the Celtics needed: a seasoned veteran who understood how to score and could provide a physical presence in the paint.

Lovellette was given the jersey number 34, a number that has since been worn by several Celtics players but has never been officially retired, a testament to its relative anonymity in the team’s history. Lovellette’s role with the Celtics was unlike any he had ever known. For the first time in his professional career, he was a true backup, and his minutes were limited. In the 1962-63 season, he appeared in 61 games, averaging just 9.2 points and 5.4 rebounds in 12.8 minutes per game. These numbers, while modest by his career standards, were highly effective. He gave the Celtics a different look, a reliable post scorer who could go to work on the block and draw fouls.

The contrast between Lovellette’s game and the Celtics’ overarching philosophy was a subtle but important part of his time in Boston. Lovellette was a throwback, a big man who operated in the half-court, using his strength and repertoire of hooks and jump shots to get his points. The Celtics, meanwhile, were a symphony of fast breaks and selfless passing. Russell would grab a rebound and immediately fire an outlet pass to Cousy or Jones, who would race up the court for an easy basket. Lovellette had to adapt, and he did so with a veteran’s grace. He understood his role and didn’t try to force his game into a system where it didn’t belong. He embraced the selfless “Celtics’ way,” proving that he could be a valuable piece even when he wasn’t the star.

His first season with the Celtics ended in glory. The team, as expected, marched through the playoffs and defeated the Los Angeles Lakers in a thrilling six-game series to win the 1963 NBA championship. Lovellette was a small but crucial part of that victory, his contributions often coming in key moments off the bench. He had done what few players are willing to do: accepted a significant reduction in role and status for the chance to win at the highest level.

The following season, 1963-64, was more of the same, though Lovellette’s role diminished slightly. He appeared in 45 games, averaging just 6.7 points and 4.2 rebounds in 9.7 minutes per game. The team was still a juggernaut, with Havlicek continuing his ascent and the core group of Russell, Cousy, and Jones still dominating the league. They once again proved to be the league’s best, defeating the San Francisco Warriors in a five-game Finals series to win their sixth championship in eight years. Lovellette had earned his second consecutive ring with the Celtics, a testament to his value as a professional.

After the 1963-64 season, Lovellette, at the age of 34, decided to retire from professional basketball. He walked away from the game a champion, having been a part of two of the most dominant teams in the sport’s history. His time in Boston was brief—just two seasons—and he was never a marquee player, but his presence was a clear sign of the Celtics’ focus on perfection and roster depth.

The reason his story is so often forgotten is simple: his legacy is far more tied to his college and early pro career. He is a Hall of Fame player, but he was inducted more for his accomplishments with the Kansas Jayhawks and the Minneapolis Lakers than for his role as a backup for the Celtics. In Boston, he was a footnote in a larger narrative, a valuable but interchangeable piece of a dynasty that was already firmly established. He was a champion, but he was not a “Celtics legend” in the same way as Russell or Havlicek.

Clyde Lovellette’s story with the Boston Celtics is a fascinating microcosm of the team’s dynasty. It’s a reminder that a team’s success is not just about its stars but about the collective effort of every player, from the starters to the last man on the bench. Lovellette’s willingness to adapt, to sacrifice his individual numbers for the good of the team, and to accept a new role late in his career speaks volumes about his character and his commitment to winning. He came to Boston a celebrated scorer and left as a two-time champion, his time with the Celtics, though often overlooked, a quiet but integral part of their storied past.

Leave a Reply